How to Write a Children’s Book That Rocks!

Thinking of writing a children’s storybook?

As an independent publisher, I often get calls from men and women who have either written a kids’ story or have one in mind they want to write. This article will focus primarily on how to write a children’s book for three- to eight-year-olds.

Many ask for tips on how to go about writing a book for children. Of those who have already written one, a high percentage would have benefited from reading a few contemporary kids’ books before sitting down to write.

The most common misconception about writing a kids’ book is that it’s a no-brainer—that after all, it’s just for kids. Listen up: Kids can be tough critics! Writing for children is not so easy as it appears. Just sitting down and knocking out 250 to 1,000 words may sound easy, but those words have a big job to do.

What Story Elements Do You Need?

Once you know the story you want to write, check to see that your story answers the age-old questions, Who? What? When? Where? and How?. A story needs a setting (time and place), one or more engaging characters, an opening that captures the reader’s interest, a plausible sequence of events (storyline) that build emotional tension (the storyline), and an unpredictable ending that resolves the tension.

What else? The topic must be relevant to a child’s world, and the style and tone consistent with a child’s emotional and intellectual development level. Some children mature more quickly than others, of course, but here are some general age readiness guidelines:

Reader Age Groups, Style, Length

Two-to-four-year-olds love repetition and respond to pictures and simple concepts like animal sounds, counting, the alphabet, and the noises made by cars, trucks and trains. Books for this age group are short; 250 words is a good number, with under fifteen words per page.

Five-year-olds consider such books “baby stories.” They are ready for a real story with lots of pictures, told in short sentences with an unfamiliar word introduced here and there to challenge them. The images should add information to the story and help the child relate emotionally to the characters. Youngsters in this age group respond well to simple alliteration, rhythm, and rhyme, and will memorize a story word for word. Rhyme and rhythm make the story more fun and facilitate memorization. Make every word count; the ideal for this age group is 500 words.

Primary school kids still enjoy picture books even though they are learning to read. These early readers—ages 6 to 8—are ready for longer stories 1.000 or even 1500 words in length. They still favor color pictures, but as they learn to read the importance of full-page color illustrations fades away. Repetitive use of words that may be new to them helps with learning new vocabulary. Sentence length should ideally still be kept to a maximum of twenty words.

Once the kids hit age eight or nine, they’re ready to leave picture books behind in favor of simple chapter books peppered with color or black-and-white illustrations. They expect to read longer books, which gives you more time in which to build up to the story’s climax.

Literary Devices

Literary devices that add sizzle for all ages—adults too—include sentence rhythm, alliteration, onomatopoeia, metaphor, and varying the sentence length.

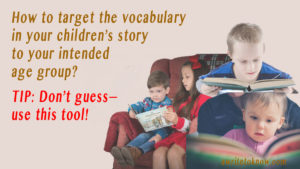

Vocabulary and Sentence Length

A major stumbling block for most adults in writing a children’s book has to do with the vocabulary level and sentence length appropriate to each age group. Do you remember what words you knew when you were six? Nine? Eleven? Probably not. Graded word lists and tools to analyze readability can be useful for targeting vocabulary levels to your target age group. One of the most popular is www.lexile.com, where you can use their Text Analyzer to obtain valuable feedback for free.

TIP: It’s better to err on the side of complexity. Most children love to learn and hate being talked down to. Besides, parents often read the books aloud and thus can explain word meanings.

As you can see, there’s a lot to consider in planning out the 100 to 1,000 words you’ll write into a children’s book.

Story Themes for Five-to-Eight-Year-Olds

Themes young children find engaging include:

- Good versus Evil

- Birth and Death

- Family and Friendship

- Love and Belonging

- Fairness and Injustice

- Courage and Heroism

- Betrayal

- Gain and Loss

- Grief and Suffering

- Power and Corruption

- Anger and Frustration

- Growing up

- Prejudice

- Survival.

This list is fairly all-encompassing, though you could come up with others, and two or more themes often overlap in a single story.

Note that we’ve been speaking of themes, not story topics. Themes have universal emotional appeal. You could use any of these themes to write about any topic you choose.

For example, the theme of power and corruption might apply equally well to a story about a battle between two dogs over dumpster scraps, making it through the school cafeteria lunch line, and an inner battle between conscience and the temptation to raid the cookie jar.

You may not find it essential to focus overtly on theme when you begin setting up your story, but an awareness of the different themes can offer insight into how to develop the story.

The line between theme and plot is not always clear. In general, theme is a more universal concept having to do with the overarching issues of the story, while plot is the category of storyline involved.

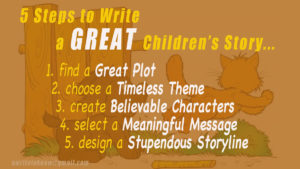

Choosing a Plot for Your Story

Choosing a plot is an essential first step in developing a story, for plot is the hinge on which the story hangs.

Most stories are based on one of seven basic plots:

- Overcoming the Monster—In stories based on this plot, the protagonist sets out to defeat an antagonistic or evil force, persevering in the face of trial and hardship until the breakthrough moment when the monster is subdued, whether by force, wit or kindness(I discuss this plot in great detail below.)

- Rags to Riches—This is the underdog story, in which an impoverished protagonist does what it takes, against all odds, to move up to financial, spiritual or other wealth. Stories of sports teams coming from behind to win grand competitions follow this plot line.

- The Quest—The protagonist sets out to find something and, after many trials, finds the object of his or her search. The story of the holy grail is the most famous story based on this plot.

- Voyage and Return—The hero sets out on a journey into some new environment (often but not always geographically defined) wherein he or she encounters tremendous challenges and returns having gained a certain wisdom. The Hare and The Tortoise and Alice In Wonderland are good examples of this plot.

- Comedy—The real challenge in stories making use of this plot is less for the protagonist, for whom life is bright and gay, than for the confused reader who tries to make sense of a continuous parade of silly misunderstandings and coincidences. Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, adapted as a children’s story, is a wonderful example.

- Tragedy—The classical definition of this plot has to do with the protagonist’s personal failings being his or her undoing. The Wile E. Coyote books, in which Coyote continually outsmarts himself, are wonderful examples.

- Rebirth—The protagonist encounters an event that forces them to change their ways, often leading to their becoming a better person. Beauty and the Beast and The Snow Queen are good examples of this plot.

The first four of these plots can be subsumed under Carl Jung’s “Hero’s Journey” heading, as in all four the protagonist starts out to overcome a challenge, overcomes one obstacle after another, and finally triumphs.

The “Overcoming the Monster” Children’s Story Plot

The “Overcoming a Monster” plot undoubtedly dates back to caveman times. It is so popular that I want to give it special attention here.

In children’s books, the monster is often just that—a monster. A delightful example is Julia Davidson’s The Gruffalo, in which a mouse makes up a monster that suddenly becomes real, at which point he tricks it into being scared of him.

But there are other kinds of monsters, both external and internal: In Little Red Riding Hood, we have the big bad wolf. In Mor and Makover’s Mary and the Scary Cloud, the monster is . . . you guessed it: a cloud. Randle and Monique’s Hey You, I Ain’t Afraid of You is a modern story of inner triumph, namely overcoming the fear of bullies.

The monster in Robert Coles’s The Story of Ruby Bridges (a true story), for example, is racism personified by angry New Orleans Whites who pull their children out of school when Ruby, a six-year-old Black girl, registers there in 1960.

After making the daily trek to school month after month with armed guards provided under Presidential order, Ruby finally triumphs when her courage inspires other African American children to join her, again when (several years later) the White families re-enroll their children in the school, and finally when she graduates from an integrated high school.

The Story of Ruby Bridges exemplifies two of the above-mentioned themes, courage and prejudice, in a story of the triumph of one over the other.

Planning Your Story: Characters and Storyline

Which comes first, characters or storyline? You can start with either. Sometimes a storyline brainstorm suggests the perfect protagonist, and sometimes the characters come first and tell you the story. Either way, you need both.

Your story may be fantasy, but your characters have to be believable. That doesn’t mean they can’t be dragons or talking cups; it just means they have to behave in ways consistent with the physical attributes, personality and intelligence you give them. They need to start in character and stay in character.

Let’s say your main character is Joey, a talking milk mug with a heart of gold and a jagged chip in his handle where the white ceramic shows through. How did Joey get his chip? Maybe he got it the day he was pushed off the shelf by the big, tall coffee mug, and now he trembles in fear of heights and cliffs and doesn’t trust the coffee mug at all.

Maybe Joey started out red, but the fall scared him so badly he turned a pale shade of green. Can you feel a storyline developing here? Perhaps this is the story of how Joey gets his red back.

What about the big, tall coffee mug? Is he a bully, always pushing the other cups around, as Joey believes, or did he nudge Joey by accident that day, wiggling to find a more comfy space on the shelf?

What Message Do You Want to Deliver?

How does Joey finally overcome his fear? The answer to that question depends on the message you want to deliver. Maybe you want Joey to realize he needs to stand up to the big, tall coffee mug. But how? He realizes he’ll never win a physical fight.

So now you work in a second message, about the importance of listening to your inner voice. Joey’s inner voice is whispering that he needs to find another way. “Put yourself in Coffee Mug’s shoes,” it whispers. So Joey does that, in his mind he becomes Coffee Mug. And he realizes he’s the big goofus on a shelf with five little mugs. He’s so out of place!

Suddenly Joey feels sorry for him. Now it’s easy to confront his fear, because he’s just transformed Coffee Mug from monster to goofus.

What other message could you choose to deliver instead? How about the value of teamwork? Joey could overcome his fear by organizing the other cups to corner Coffee Mug in the back of the shelf so he’ll never get noticed or taken out for a drink.

Or maybe you want to make the point that even a bully can be won over with love, or that cups (people) aren’t always what they seem to be, in which case Joey’s discovery that the big, tall coffee mug has marshmallow insides (Ooh, think of the fun you could have with that!) lays his fear to rest.

Your message is what determines where your story goes, otherwise known as the storyline.

If you have a children’s book storyline you want some help with, no matter where you are in the process of developing your story, feel free to contact me for a personal coaching session. Email me at AWriteToKnow@gmail.com using the subject line “I need help with my children’s book.” Tell me what you need help with. I offer a free 15-minute consultation; I’ll explain the pricing from there on depending on what you need. A little coaching can make the writing more fun, help you create a better book, and save you time and money. Let me hear from you!

Founder, AWritetoKnow.com, GreenSongPress.com, EcoActive101.com, PetWrites.com

Facebook: https://facebook.com/chiwah.slater, https://facebook.com/thepluckyducky, https://facebook.com/ecoactive101

Pinterest: http://www.pinterest.com/chiwahslater

LinkedIn: http://www.linkedin.com/in/chiwah

Twitter: https://twitter.com/PetWrites

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCQvxaLnSFpXmtjWBd1fFEUw